Elizabeth Soberanes San Francisco War Memorial Performing Arts Center

| Elizabeth Catlett | |

|---|---|

Elizabeth Catlett, 1986 (photograph past Fern Logan) | |

| Born | Alice Elizabeth Catlett[1] (1915-04-xv)Apr 15, 1915 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Died | April 2, 2012(2012-04-02) (anile 96)[2] Cuernavaca, Mexico |

| Nationality | United states of america, Mexico |

| Other names | Elizabeth Catlett Mora |

| Instruction | School of the Art Found of Chicago, S Side Community Art Centre |

| Alma mater | Howard University, University of Iowa |

| Occupation | sculptor, art instructor, graphic creative person |

| Employer | Taller de Gráfica Popular, Faculty of Arts and Blueprint |

| Works | Students Aspire |

| Spouse(south) | Charles Wilbert White (m. 1941–1946; divorced) Francisco Mora (painter) (m. 1947–2002; his decease) |

| Children | three, including Juan Mora Catlett |

| Website | www |

Elizabeth Catlett, born as Alice Elizabeth Catlett, also known as Elizabeth Catlett Mora (April 15, 1915[one] – April ii, 2012)[3] [iv] was an African American sculptor and graphic creative person best known for her depictions of the Black-American feel in the 20th century, which oft focused on the female person feel. She was born and raised in Washington, D.C., to parents working in education, and was the grandchild of formerly enslaved people. Information technology was difficult for a black woman at this time to pursue a career as a working creative person. Catlett devoted much of her career to teaching. Notwithstanding, a fellowship awarded to her in 1946 immune her to travel to Mexico Metropolis, where she worked with the Taller de Gráfica Popular for 20 years and became caput of the sculpture department for the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. In the 1950s, her main means of artistic expression shifted from print to sculpture, though she never gave up the sometime.

Her work is a mixture of abstract and figurative in the Modernist tradition, with influence from African and Mexican fine art traditions. Catlett's work can be described every bit social realism, because of her dedication to the issues and experiences of African Americans.[v] According to the creative person, the primary purpose of her work is to convey social letters rather than pure aesthetics. Her work is heavily studied by art students looking to depict race, gender and class issues. During her lifetime, Catlett received many awards and recognitions, including membership in the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana, the Art Establish of Chicago Legends and Legacy Award, honorary doctorates from Step University and Carnegie Mellon, and the International Sculpture Heart's Lifetime Achievement Award in contemporary sculpture.

Early on life [edit]

Catlett was born and raised in Washington, D.C.[3] [6] Both her mother and male parent were the children of freed slaves, and her grandmother told her stories about the capture of their people in Africa and the hardships of plantation life.[6] [7] [8] Catlett was the youngest of three children. Both of her parents worked in teaching; her female parent was a truant officer and her father taught math at Tuskegee University, the then D.C. public school arrangement.[1] Her father died before she was born, leaving her mother to hold several jobs to support the household.[1] [6] [viii]

Catlett's interest in art began early. As a kid she became fascinated by a forest carving of a bird that her male parent fabricated. In high school, she studied art with a descendant of Frederick Douglass.[seven]

Didactics [edit]

Catlett completed her undergraduate studies at Howard University, graduating cum laude, although it was not her outset option.[1] [9] She was also admitted into the Carnegie Institute of Technology but was refused admission when the school discovered she was black.[ane] [six] However, in 2007, as Cathy Shannon of Due east&S Gallery was giving a talk to a youth group at the August Wilson Middle for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, PA, she recounted Catlett'south necktie to Pittsburgh considering of this injustice. An administrator with Carnegie Mellon University was in the audition and heard the story for the commencement fourth dimension. She immediately told the story to the school's president, Jared Leigh Cohon, who was besides unaware and securely appalled that such a affair had happened. In 2008, President Cohon presented Catlett with an honorary Doctorate degree and a 1-woman show of her art was presented past E&S Gallery at The Regina Gouger Miller Gallery on the campus of Carnegie Mellon University.[ten] [11]

At Howard Academy, Catlett'southward professors included artist Lois Mailou Jones and philosopher Alain Locke.[half dozen] She also came to know artists James Herring, James Wells, and future fine art historian James A. Porter.[vii] [12] Her tuition was paid for past her mother's savings and scholarships that the creative person earned, and she graduated with honors in 1937.[two] [1] [3] [six] At the time, the idea of a career equally an artist was far-fetched for a black woman, so she completed her undergraduate studies with the aim of beingness a teacher.[7] After graduation, she moved to her mother's hometown of Durham, N Carolina to teach art at Hillside Highschool.[i] [7]

Catlett became interested in the work of American painter Grant Forest, and so she entered the graduate program where he taught, at the University of Iowa.[i] In that location, she studied drawing and painting with Forest,[13] also as sculpture with Harry Edward Stinson.[14] Forest advised her to depict images of what she knew best, and so Catlett began sculpting images of African-American women and children.[1] [15] Notwithstanding, despite being accepted to the school, she was not permitted to stay in the dormitories; therefore, she rented a room off-campus.[xiv] One of her roommates was futurity novelist and poet Margaret Walker.[vii] Catlett graduated in 1940, i of 3 to earn the start Masters in Fine Arts from the academy, and the first African-American woman to receive the degree.[2] [3] [14]

Later Iowa, Catlett moved to New Orleans to work at Dillard University, spending the summer breaks in Chicago. During her summers, she studied ceramics at the School of the Fine art Found of Chicago and lithography at the S Side Customs Art Center.[3] [12] In Chicago, she also met her showtime husband, artist Charles Wilbert White. The couple married in 1941.[3] [vii] [16] In 1942, the couple moved to New York, where Catlett taught adult instruction classes at the George Washington Carver Schoolhouse in Harlem. She also studied lithography at the Art Students League of New York, and received private educational activity from Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine,[3] [12] who urged her to add abstruse elements to her figurative piece of work.[ane] During her time in New York, she met intellectuals and artists such every bit Gwendolyn Bennett, West. E. B. Dubois, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and Paul Robeson.[7] [viii]

In 1946, Catlett received a Rosenwald Fund Fellowship to travel with her husband to Mexico and report.[6] She accustomed the grant in role considering at the time American art was trending toward the abstruse while she was interested in fine art related to social themes.[7] Shortly after moving to Mexico that same twelvemonth, Catlett divorced White.[sixteen] In 1947, she entered the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a workshop dedicated to prints promoting leftist social causes and instruction. There she met printmaker and muralist Francisco Mora, whom she married later that aforementioned yr.[3] [12] [16] The couple had three children, all of whom developed careers in the arts: Francisco in jazz music, Juan Mora Catlett in filmmaking, and David in the visual arts. The last worked every bit his mother's assistant, performing the more labor-intensive aspects of sculpting when she was no longer able.[7] [8] [17] In 1948, she entered the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda" to report woods sculpture with José L. Ruíz and ceramic sculpture with Francisco Zúñiga.[iii] During this time in Mexico, she became more serious nearly her fine art and more dedicated to the work information technology demanded.[12] She as well met Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.[8]

In 2006, Kathleen Edwards, the curator of European and American art, visited Catlett in Cuernavaca, United mexican states and purchased a group of 27 prints for the University of Iowa Museum of Art (UIMA).[18] Catlett donated this money to the University of Iowa Foundation in social club to fund the Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship Fund, which supports African-American and Latino students studying printmaking.[14] Elizabeth Catlett Residence Hall on the University of Iowa campus is named in her award.[nineteen]

Activism [edit]

Catlett worked with the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) from 1946 until 1966. However, because some of the members were besides Communist Political party members, and considering of her own activism regarding a railroad strike in Mexico City led to an arrest in 1949, Catlett came nether surveillance by the United states Embassy.[one] [16] [xx] Somewhen, she was barred from entering the United States and declared an "undesirable alien." She was unable to return home to visit her ill mother before she died.[vii] In 1962, she renounced her American citizenship and became a Mexican citizen.[1] [iii] [12]

In 1971, after a letter-writing campaign to the Land Department by colleagues and friends, she was issued a special permit to attend an exhibition of her work at the Studio Museum in Harlem.[1] [7]

Later years [edit]

Later on retiring from her didactics position at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Catlett moved to the urban center of Cuernavaca, Morelos in 1975.[1] In 1983, she and Mora purchased an apartment in Battery Park City, New York. The couple spent role of the yr in that location together from 1983 until Mora's death in 2002.[1] [8] [16] Catlett regained her American citizenship in 2002.[8] [12]

Catlett remained an active creative person until her death.[6] [20] The artist died peacefully in her slumber at her studio home in Cuernavaca on April 2, 2012, at the age of 96.[2] [three] She is survived past her iii sons, x grandchildren, and 6 great-grandchildren.[ane]

Career [edit]

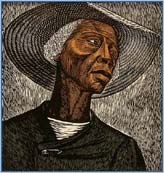

Sharecropper, 1952[21] or 1957[22]

Very early on in her career, Catlett accustomed a Public Works of Art Project assignment with the federal government for unemployed artists during the 1930s. Withal, she was fired for lack of initiative, very likely due to immaturity. The experience gave her exposure to the socially-themed work of Diego Rivera and Miguel Covarrubias.[7]

Much of her career was spent pedagogy, equally her original intention was to be an art teacher. After receiving her undergraduate degree, her kickoff teaching position was in the Durham, North Carolina school system. She taught art at Hillside High Schoolhouse. However, she became very dissatisfied with the position because black teachers were paid less. Forth with Thurgood Marshall, she participated in an unsuccessful campaign to gain equal pay.[12] After graduate school, she accepted a position at Dillard University in New Orleans in the 1940s. There, she arranged a special trip to the Delgado Museum of Art to meet the Picasso exhibit. As the museum was closed to black people at the time, the group went on a day information technology was closed to the public.[i] She eventually went on to chair the art department at Dillard.[7] Her adjacent teaching position was with the George Washington Carver School, a community alternative school in Harlem, where she taught art and other cultural subjects to workers enrolled in night classes.[7] Her last major teaching position was with the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (now known every bit the Faculty of Arts and Design) at the National Democratic University of Mexico (UNAM), starting in 1958, where she was the first female professor of sculpture.[ane] 1 twelvemonth later, she was appointed the head of the sculpture department despite protests that she was a woman and a foreigner.[12] [16] She remained with the schoolhouse until her retirement in 1975.[23]

When she moved to United mexican states, Catlett's starting time work as an creative person was with the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a famous workshop in Mexico City dedicated to graphic arts promoting leftist political causes, social issues, and teaching. At the TGP, she and other artists created a serial of linoleum cuts featuring prominent blackness figures, too as posters, leaflets, illustrations for textbooks, and materials to promote literacy in Mexico.[24] Sharecropper, one of the linoleum cuts made at the TGP, is possibly her most famous work and is an excellent instance of Catlett's bold visual fashion due to both the well-baked blackness lines and rich brownish and green inks of the drawing, and the halo of the hat brim and the upwardly looking angle of the composition making the figure monumental, or someone to be venerated, despite the poverty evidenced by the safety pin belongings together the cloak.[21] [22] [25] Catlett's immersion into the TGP was crucial for her appreciation and comprehension of the signification of "mestizaje", a blending of Indigenous, Spanish and African antecedents in Mexico, which was a parallel reality to the African American experiences.[26] She remained with the workshop for twenty years, leaving in 1966.[27] Her posters of Harriet Tubman, Angela Davis, Malcolm X and other figures were widely distributed.[1]

Although she had an individual exhibition of her work in 1948 in Washington, D.C.,[3] her work did not begin to be shown regularly until the 1960s and 1970s, almost entirely in the United States,[3] [20] where it drew interest because of social movements such as the Black Arts Movement and feminism.[1] [16] While many of these exhibitions were commonage, Catlett had over fifty individual exhibitions of her work during her lifetime.[1] [6] Other of import private exhibitions include Escuela Nacional de Arte Pláticas of UNAM in 1962, Museo de Arte Moderno in 1970, Los Angeles in 1971, the Studio Museum in Harlem in New York in 1971, Washington, D.C. in 1972, Howard University in 1972, Los Angeles Canton Museum of Art in 1976, Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon Academy in 2008,[2] [10] and the 2011 individual show at the Bronx Museum. From 1993 to 2009, her work was regularly on brandish at the June Kelly Gallery.[two] In July 2020, while closed to the public during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philadelphia Museum of Art featured Catlett'southward piece of work in an online showroom.[28]

The Legacy Museum, which opened on April 26, 2018,[29] displays and dramatizes the history of slavery and racism in America and features artwork by Catlett and others.[thirty]

Awards and recognition [edit]

During Catlett'southward lifetime she received numerous awards and recognitions.[12] These include First Prize at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago,[31] consecration into the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana in 1956,[3] the Distinguished Alumni Honour from the University of Iowa in 1996,[14] a 1998 50-twelvemonth traveling retrospective of her work sponsored by the Newberger Museum of Art at Purchase College,[2] [three] a NAACP Image Honour in 2009,[20] and a joint tribute later her death held by the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana and the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in 2013.[iii] Others include an accolade from the Women's Conclave for Fine art, the Art Institute of Chicago Legends and Legacy Award, Elizabeth Catlett Week in Berkeley, Elizabeth Catlett Day in Cleveland, honorary citizenship of New Orleans, honorary doctorates from Pace University and Carnegie Mellon, and the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement Award in contemporary sculpture. The Taller de Gráfica Popular won an international peace prize in part because of her achievements .[8] [12] [x] She received a Candace Honor from the National Coalition of 100 Blackness Women in 1991.[32]

Past the end of her career, her works, especially her sculptures, sold for tens of thousands of dollars.[seven]

In 2017, Catlett's alma mater, the Academy of Iowa, opened a new residence hall that bears her name.

Catlett was the subject of an episode of the BBC Radio 4 serial An Alternative History of Art, presented past Naomi Beckwith and broadcast on March half-dozen, 2018.[33] The Philadelphia Museum of Fine art featured her in an online exhibition

Artistry [edit]

Catlett is recognized primarily for sculpting and print piece of work.[3] Her sculptures are known for being provocative, merely her prints are more widely recognized, mostly because of her piece of work with the Taller de Gráfica Popular.[three] [7] Although she never left printmaking, starting in the 1950s, she shifted primarily to sculpture.[16] Her print work consisted mainly of woodcuts and linocuts, while her sculptures were equanimous of a diversity of materials, such equally clay, cedar, mahogany, eucalyptus, marble, limestone, onyx, bronze, and Mexican stone (cantera).[1] [12] She ofttimes recreated the same piece in several different media.[17] Sculptures ranged in size and scope from small wood figures inches high to others several feet alpine to awe-inspiring works for public squares and gardens. This latter category includes a x.5-foot sculpture of Louis Armstrong in New Orleans and a 7.5-human foot piece of work depicting Sojourner Truth in Sacramento.[7]

Much of her piece of work is realistic and highly stylized 2- or 3-dimensional figures,[six] applying the Modernist principles (such as organic abstraction to create a simplified iconography to display man emotions) of Henry Moore, Constantin Brâncuși and Ossip Zadkine to pop and hands recognized imagery. Other major influences include African and pre-Hispanic Mexican art traditions. Her works exercise not explore individual personalities, non even those of historical figures; instead, they convey abstracted and generalized ideas and feelings.[16] Her imagery arises from a scrupulously honest dialogue with herself on her life and perceptions, and between herself and "the other", that is, contemporary lodge's beliefs and practices of racism, classism and sexism.[34] Many young artists written report her work as a model for themes relating to gender, race and grade, only she is relatively unknown to the general public.[20]

Mother and Kid, 1939

Her work revolved effectually themes such as social injustice, the human condition, historical figures, women and the human relationship between mother and child.[16] These themes were specifically related to the African-American feel in the 20th century with some influence from Mexican reality.[2] [1] [12] This focus began while she was at the University of Iowa, where she was encouraged to depict what she knew all-time. Her thesis was the sculpture Mother and Child (1939), which won first prize at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago in 1940.[fifteen]

Her subjects range from sensitive maternal images to confrontational symbols of Blackness Ability, and portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm Ten, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and writer Phyllis Wheatley,[half-dozen] [17] as she believed that fine art tin play a role in the construction of transnational and ethnic identity.[ citation needed ] Her best-known works depict black women as potent and maternal.[i] [20] The women are voluptuous, with broad hips and shoulders, in positions of power and confidence, frequently with torsos thrust forward to show attitude. Faces tend to be mask-like, generally upturned.[7] Female parent and Kid (1939) shows a immature woman with very short hair and features like to that of a Gabon mask. A tardily work Bather (2009) has a like subject flexing her triceps.[1] Her linocut series The Blackness Woman Speaks, is among the starting time graphic series in Western art to depict the image of the American black adult female every bit a heroic and complex homo.[34] : 46 Her work was influenced by the Harlem Renaissance move[3] and the Chicago Black Renaissance in the 1940s and reinforced in the 1960s and 1970s with the influence of the Black Power, Blackness Arts Motion and feminism.[16] With artists like Lois Jones, she helped to create what critic Freida Tesfagiorgis called an "Afrofemcentrist" analytic.[31]

The Taller de Gráfica Popular pushed her to adjust her piece of work to reach the broadest possible audience, which mostly meant balancing brainchild with figurative images. She stated of her time at the TGP, "I learned how you lot use your art for the service of people, struggling people, to whom only realism is meaningful."[one]

Critic Michasel Brenson noted the "fluid, sensual surfaces" of her sculptures, which he said "seem to welcome non only the cover of low-cal simply also the caress of the viewer's hand." Ken Johnson said that Ms. Catlett "gives wood and stone a melting, well-nigh erotic luminosity." But he also criticized the iconography equally "generic and clichéd."[i]

Notwithstanding, Catlett was more concerned in the social messages of her piece of work than in pure aesthetics. "I have always wanted my fine art to service my people – to reflect us, to chronicle to u.s.a., to stimulate united states of america, to make the states aware of our potential."[one] She was a feminist and an activist earlier these movements took shape, pursuing a career in fine art despite segregation and the lack of female person role models.[1] [12] "I don't recollect fine art can change things," Catlett said: "I recall writing can practice more. But art can prepare people for change, it tin be educational and persuasive in people's thinking."[7]

Catlett as well acknowledged her artistic contributions as influencing younger black women. She relayed that being a black woman sculptor "before was unthinkable. ... At that place were very few blackness women sculptors – maybe five or six – and they all have very tough circumstances to overcome. You can be black, a woman, a sculptor, a impress-maker, a teacher, a mother, a grandmother, and keep a business firm. It takes a lot of doing, just yous can do information technology. All you lot have to exercise is decide to do it."[seven]

Catlett's series The Negro Woman dated 1946–1947, is a series of 15 linoleum cuts that highlight the experience of bigotry and racism that African American Women were facing at the time. This series also highlighted the forcefulness and heroism of these women illustration women including the historically prominent African American women Harriet Tubman and Phillis Wheatley.[35]

Artist statements [edit]

No other field is closed to those who are not white and male person as is the visual arts. Later on I decided to be an creative person, the first thing I had to believe was that I, a blackness woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, farther, I could do and then without sacrificing one iota of my blackness or my femaleness or my humanity.

—Elizabeth Catlett, 1973[36]

"Art for me must develop from a necessity within my people. Information technology must reply a question, or wake somebody up, or give a shove in the correct direction — our liberation."[37]

Works [edit]

This is a list of select piece of work by Catlett.

- Students Aspire (1977), Howard Academy campus, 2300 6th Street NW, Washington, D.C.

- For My People portfolio (published 1992), by Limited Editions Club, New York

- Ralph Ellison Memorial (2002), 150th Street and Riverside Drive, Manhattan, New York[38]

- Torso (1985),[39] is a carving in mahogany modeled later on another of Catlett's pieces, Pensive (b. 1946)[40] a bronze sculpture. The mahogany carving is in the York Higher, CUNY Fine Art Collection (dimensions: 35' H 10 19' W x 16' D). The exaggerated arms and breasts are prominent features of this slice. The crossed arms are wide, with simple geometric shapes and ripples to point a shirt with rolled-upward sleeves, along with a gentle ridge along the cervix. The easily are carved larger than what would be in proportion to the trunk. The effigy's eyes are painted with a calm, yet steady gaze that signifies confidence. Catlett evokes a strong, working-class blackness adult female like to her other pieces that she created to portray women's empowerment through expressive poses. Catlett favored materials such as cedar and mahogany because these materials naturally depict brown skin.

Collections [edit]

- Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania[10]

- Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), Detroit, Michigan

- Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico Metropolis, Mexico[1] [3] [2]

- Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York Metropolis, New York[41] [31]

- Miami-Dade Public Library System, Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), Minneapolis, Minnesota[42]

- Minnesota Museum of American Art, St. Paul, Minnesota

- Museum of Modernistic Art (MoMA), New York Metropolis, New York[43]

- National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C.[44]

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[45]

- Reginald F. Lewis Museum, Baltimore, Maryland[46]

- Schomburg Center for Inquiry in Black Civilisation, New York City, New York[7]

- Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio[47]

- University of Iowa, Iowa Urban center, Iowa[14]

- Whitney Museum of American Fine art, New York City, New York[48]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j k 50 grand northward o p q r s t u v w ten y z aa ab ac ad ae Karen Rosenberg (April iii, 2012). "Elizabeth Catlett, Sculptor With Heart on Social Bug, Is Dead at 96". New York Times . Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Boucher, Brian (April 3, 2012). "Elizabeth Catlett, 1915–2012". Art in America mag . Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j g 50 chiliad n o p q r s t Mujeres del Salón de la Plástica Mexicana. Vol. 1. Mexico Metropolis: CONACULTA/INBA. 2014. pp. 60–61. ISBN978-607-605-255-6.

- ^ "Conversation: The Life, Work and Legacy of Elizabeth Catlett, 1915-2012". PBS NewsHour. 2012-04-05. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ Bateman, Anita (April 2016). "Narrative and Seriality in Elizabeth Catlett's Prints". Journal of Black Studies. 47 (3): 258. doi:x.1177/0021934715623780. S2CID 146427495.

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j k "Elizabeth Catlett 1915–2012". National Museum for Women in the Arts. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i j m fifty m n o p q r s t u v "Elizabeth Catlett". Sally. 11 (5): 46–51. March 2000.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thousand h "Elizabeth Catlett". International Sculpture Heart. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Riggs, Thomas (Jan 1, 1997). St. James guide to blackness artists. Detroit: St. James Press published in association with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. ISBN1558622209. OCLC 955223324.

- ^ a b c d "May 15: Carnegie Mellon Honors Artist Elizabeth Catlett With Special Exhibition, Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts, May 17–18". Carnegie Mellon Academy. May xv, 2008. Retrieved Feb xi, 2015.

- ^ Haynes, Monica, "Making apology: CMU lauds famed black creative person 76 years after it denied her comprisal", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l thousand n "Elizabeth Catlett". Ebony. 61 (five): 100–102, 104. March 2006.

- ^ Phaidon Editors (2019). Great women artists. Phaidon Printing. p. 93. ISBN978-0714878775.

- ^ a b c d e f "Elizabeth Catlett". University of Iowa. Retrieved Feb 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Charlotte Streifer Rubenstein (1990). American Women Sculptors. Boston: Yard.K. Hall & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j g "Elizabeth Catlett: The power of class". The World & I. 13 (seven): 118–123. July 1998.

- ^ a b c "5 Things to Know Most Elizabeth Catlett". Scholastic Art. 42 (4): ten. February 2012.

- ^ "I Am: Prints by Elizabeth Catlett".

- ^ "Catlett Residence Hall | Campus Maps & Tours". maps.uiowa.edu . Retrieved 2018-08-10 .

- ^ a b c d e f Keyes, Allison (Feb 12, 2012). "Blackness, Female person And An Inspirational Modern Artist". National Public Radio. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett". Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Taller de Gráfica Popular". Oxford Reference . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art . Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Amy Helene Kirschke, University Press of Mississippi, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lagcc-ebooks/detail.activeness?docID=1770987.

- ^ "Fallece la escultora y grabadora Elizabeth Catlett: MÉXICO OBITUARIO". EFE News Service. Madrid. April four, 2012.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Artist in Focus: Elizabeth Catlett". philamuseum.org . Retrieved 2020-07-20 .

- ^ "Exonerated death row inmate tells his story at Legacy Museum". CBS. Apr nine, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Miller, James H. (April 16, 2018). "Alabama memorial confronts America's racist history". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved Apr 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Riggs, Thomas (1997). St. James Guide to Black Artists. St. James Press. pp. 100–2. ISBN1-55862-220-9.

- ^ "Relate". The New York Times. June 26, 1991.

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett", Episode ii, An Alternative History of Art, BBC Radio iv, March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Kearns, Martha. Gumbo Ya Ya: Album of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. New York: MidMarch Press, 1995.

- ^ Bateman, Anita (April 2016). "Narrative and Seriality in Elizabeth Catlett'south Prints". Journal of Black Studies. 47 (3): 263. doi:x.1177/0021934715623780. S2CID 146427495.

- ^ Farris, Phoebe. Women Artists of Color: A Bio-critical Sourcebook to 20th Century Artists in the Americas. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999.

- ^ Scarborough, Klare, "Elizabeth Catlett: Singing the Dejection", The International Review of African American Art, Vol. 25, No. iv, (2015), p. 51.

- ^ "Riverside Park Monuments - Ralph Ellison Memorial". NYC Parks. Archived from the original on 2014-09-07. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett". spider web.york.cuny.edu . Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Friends of Kresge presents: Gifts of Fine art: 35 Years of Friends of Kresge Acquisitions". artmuseum.msu.edu . Retrieved Dec 12, 2017.

- ^ "Head of a Woman (Adult female), 1942–44". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett". Minneapolis Constitute of Art (MIA). Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett". The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Artist Profile: Elizabeth Catlett". National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA). Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Artist in Focus: Elizabeth Catlett". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett: Artist Every bit Activist". Reginald F. Lewis Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-10-04. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "March ii Art Infinitesimal: Elizabeth Catlett, Caput of a Immature Woman". The Toledo Museum of Fine art. 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett". whitney.org. Whitney Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on 2021-07-17. Retrieved 2021-07-17 .

Further reading [edit]

- Herzog, Melanie (2000). Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico. Jacob Lawrence series on American artists. Seattle, WA: Academy of Washington Press. ISBN9780295979403.

- Dufrene, Phoebe (1994), "A Visit with Elizabeth Catlett", Art Education, National Fine art Education Association, 47 (1): 68–72, doi:ten.2307/3193443, JSTOR 3193443

- LaDuke, Betty. (1992) "African/American Sculptor Elizabeth Catlett: A Mighty Fist for Social Change," in Women Artists: Multicultural Visions. New Jersey, pp. 127–144.

- Merriam, Dena. "All History's Children: The Art of Elizabeth Catlett," Sculpture Review (vol. 42, no. iii, 1993), pp. 6–eleven.

- Tesfagiogis, Freida High Due west., "Afrofemcentrism and its Fruition in the Art of Elizabeth Catlett and Organized religion Ringold", in Norma Broude and Mary D. Carrard, eds. The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History. New York, 1992, pp. 475–86.

External links [edit]

- Listings for over lxx works produced by Elizabeth Catlett during her time at the Taller de Gráfica Pop can exist viewed at Gráfica Mexciana.

- Elizabeth Catlett Online. ArtCyclopedia guide to pictures of works by Elizabeth Catlett in art museum sites and image archives worldwide.

- Distinguished Alumni Awards. The Academy of Iowa Presents Elizabeth Catlett Mora

- Elizabeth Catlett's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

russellarehiscied.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Catlett

0 Response to "Elizabeth Soberanes San Francisco War Memorial Performing Arts Center"

Post a Comment